By Zvi Harel | Israel Today | 09.18.2018

[su_note note_color=”#fbfbec”]Dressed in battle gear, dirty,

shoes heavy with grime,

they ascend the path quietly.

To change garb,

to wipe their brow

they have not yet found time.

Still bone weary from days and from nights in the field.

From: The Silver Platter

A Poem by Natan Alterman

Written towards the end of 1947,

a few weeks after the outbreak of the War of Independence.[/su_note]

It would hardly be possible to relate the terrible story of the October 1973 Yom Kippur War – especially the dramatic turn of events that literally saved the State of Israel – without putting the 14th Brigade front and center. This standing armored brigade, under the command of Col. Amnon Reshef, played a critical role that merits greater attention. When the war broke out, the 14th was the only tank brigade defending the 200 kilometer long Suez Canal front. The strongholds along the canal were manned at the time by reservists from the 16th Jerusalem brigade along with soldiers from the Nahal brigade. As a result the 14th was virtually alone, holding the line against wave after wave of a massive Egyptian military crossing of 90,000 infantry soldiers and 820 tanks within the first 18 hours of the war on October 6th.

The 14th brigade continued to play a critical – and heroic – role throughout the war. It took part in stopping the Egyptian armored assault on October 14th; crossing the Suez Canal (Operation Stouthearted Men), breaking through the Egyptian deployment in the deadly battle of the “Chinese farm” (October 15th and 16th); and then battled on to the gates of Ismailiyah. The 14th brigade took heavy casualties in these bitter engagements, losing 302 of its men, with hundreds of others injured. 82 were killed on the first day of battle alone. Another 121 lost their lives in breaking through Egyptian lines at the Chinese farm.

Reshef was given command of the brigade about a year before the Yom Kippur War. On the eve of battle, the 14th numbered almost 1,000 soldiers. Two battalions with 56 tanks were under Reshef’s command and a third, deployed in the northern sector of the canal, was under the command of the 275th brigade. Reshef had previously led the 52nd battalion and the 189th reconnaissance battalion. He received his first battle experience as a company commander during a 1959 raid on a fortification in the Golan Heights, carried out jointly with a force from the Golani brigade. During the Six Day War he served as intelligence officer and Deputy Commander of the 8th brigade, where he fought both in the Sinai and the Golan.

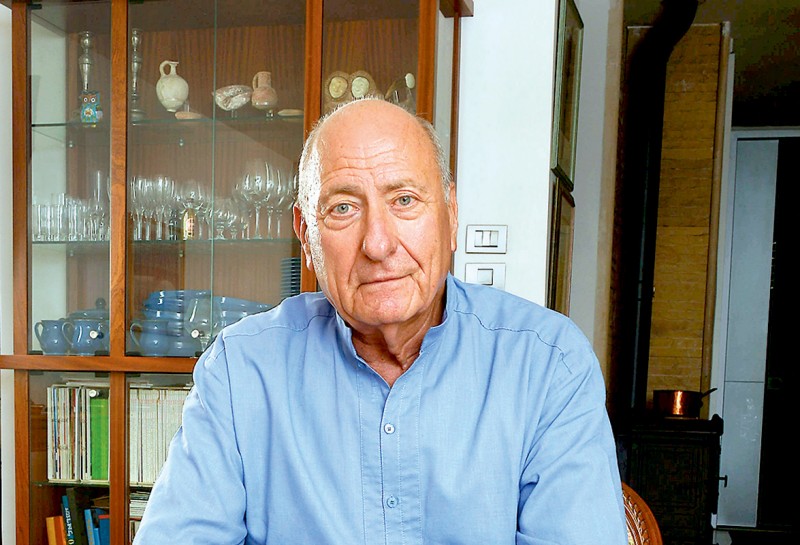

Six months after the Yom Kippur War he was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General and appointed Deputy Commander of the IDF armored division. In 1979 Reshef was given command of the IDF armored corps and raised to the rank of Major General. He retired from active duty in 1984.

In 2014 he founded Commanders for Israel’s Security, bringing together hundreds of former senior commanders from all branches of Israel’s security forces (the IDF, Mossad, Israel Security Agency and Police). Reshef, who chairs the movement, opposes the annexation of Judea and Samaria, warning that Israel will be burdened with responsibility for the civilian population there.

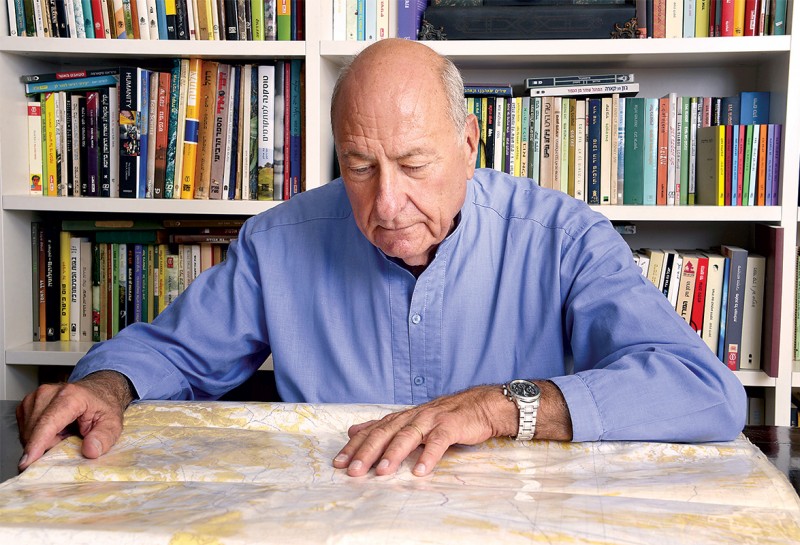

Reshef argues that the soldiers from his brigade never received due credit for putting their lives on the line during the Yom Kippur War. Even an official IDF study was riddled with factual errors on this point. Protesting these inaccuracies, Reshef convinced IDF authorities not to publish it. To set the record straight, Reshef conducted his own, painstaking research, reviewing untold quantities of documentation in the process. The resulting, 640 page book, We Will Never Cease!, was published five years ago (Kinneret Zmora-Bitan, Dvir publishers).

He dedicated the book to the fighters of the 14th brigade, to those who gave their lives and their families. We Will Never Cease! is meticulously documented. Reshef consulted the brigade’s sources, including aerial photographs, eyewitness accounts of commanders, front line soldiers, men who served in the canal strongholds and Israeli POWs; transcripts of radio communication, captured enemy documents, and transcripts of the commission of inquiry headed by Justice Shimon Agranat, — a commission in front of which Reshef testified twice (four hours each).

Now, 45 years after the war, Reshef agreed to an interview with Israel Today, sharing not only details of what happened on the battlefield but also his insights as he reflects on those momentous events.

I listened to his riveting story for hours on end. Reshef told me about his struggle to survive the blood drenched battles of the Yom Kippur War, as bullets, tank shells and Sagger missiles shrieked overhead. His performance won him the admiration, not only of his own men but of his commanding officers. Thus, for instance, Major General Yisrael Tal, Deputy Chief of Staff during the war, says “Amnon’s experience was unique. I don’t know of another commander anywhere who went through what he did that night.”

Reshef is a tall fellow (1.9 meters). Heis speaks with a calm voice and displays a phenomenal memory. “I didn’t think I’d make it,” he tells me as he describes an operation to rescue fighters trapped in the Purkan stronghold. “I was ready to pay the price. Maybe it was the sight of so many dead and injured. I really thought I was next.”

After the fighting had ended, Reshef often looked back wondering what gave him the strength to battle on in the face of death. The answer, he concludes, begins with a less than easy childhood, mired by his mother’s death when he was only 13.

Mentally Unprepared

Reshef, a father of five and grandfather to 16, was born in Haifa 80 years ago. His parents made Aliyah from Hungary in the 1920’s. Before Hebraizing it, his family’s name was Izaak. “When I was a year and a half old,” he relates, “we moved to Tel Aviv. The family was poor. The four of us – my parents, my younger brother and myself — lived in a one room, cellar apartment. My father was a tailor and our home was his workshop. But despite the scarcity, we were happy. We lacked for nothing.”

Reshef’s family was traditional. “Mainly because of my mother,” he relates. “We kept a kosher kitchen and I usually covered my head – not with a kippah, but with a beret. I sang in a children’s’ choir that performed in synagogues around Tel Aviv. “

Reshef studied in the Tel Nordau elementary school. At the end of WWII, his mother’s nephew — a survivor of the Auschwitz death camp — came to stay with them. The family came up with a creative housing solution for him, placing a basic metal bed on the balcony and enclosing it with wooden boards. Five months later, after the uncle found his own apartment, two of his sisters – Auschwitz survivors as well – came to Israel, taking his place on the balcony. “We honestly didn’t feel crowded,” Reshef recalls.

When he reached the age of 13, the family moved to a two room apartment in Bat Yam – near the sand dunes, a kilometer outside the town’s built up area, adjacent to the industrial zone. As a youth, Reshef worked in the nearby popsicle factory. After his mother died, his brother was sent to a kibbutz and then to a boarding school. Reshef stayed at home. In light of the financial situation, Reshef was advised to study at the Shevach trade school. His mother’s death was very hard on his father. She had been the dominant figure in the family. Reshef lasted only a year at school.

At 15 Reshef began working full time to support the family. He remembers working at a milling machine in a dark cubicle in Jaffa. “It wasn’t easy for a child to travel each morning to work in Jaffa and come back at 5 in the evening. Our apartment had no hot water. We used primitive methods to heat up water when we needed it.”

The turning point came at age 16, when Reshef decided to go back to school. He registered to study mechanical metalwork at the Max Fein School in the afternoon, while continuing to work full time, starting his day at 5:00 am. He maintained this exhausting routine until he was drafted into the army on the eve of the Sinai campaign, in August 1956.

Why did you chose to serve in the armored corps?

Reshef: You’ll have to ask the folks who sent me. I actually wanted to be a pilot, but I failed the vision exam at the Tel Nof base. The tank commander’s course attracted young people from all over – city kids and kibbutzniks – from well to do families. I personally didn’t choose tanks. In fact, I wasn’t an outstanding trainee. They just sent me to the armored corps training base and decided that I’d be an instructor.

As the years went by, Reshef never gave up hope of continuing his education. He wanted to complete his matriculation. Army officials made all kinds of promises, from a degree at the Technion to studying in the US. But in the end, they never came through, appealing instead to his sense of duty. Reshef blames the commanders of the armored corps, including Yisrael Tal and Avraham Adan, who failed to make good on their promises. He recalls an emotionally charged meeting right after the Six Day War, when General Tal asked him to assume command of a tank battalion. “I was tense going into the meeting. I told him to forget about it. I said it was time to deliver on what was promised. Tal played on my sense of guilt, reminding me of our fallen comrades. He promised that after this commission, all kinds of possibilities would open up. ‘You can study in the US, whatever you want,’ he told me. He put me in an impossible situation. We all knew the guys who had lost their lives. It was only after being released from military service, having reached the rank of major general, that I was able to study for a B.A. in history at Tel Aviv University. I graduated with honors, despite never having completed my high school matriculation.”

Our discussion proceeds to the eve of the Yom Kippur War. In June of 1973, the brigade conducted a challenging exercise – a night time assault, with no dry run. We were at the peak of our training, ready for action. A few days before the war, Reshef’s soldiers reported unusual Egyptian troop movements, along with the arrival of reinforcements. He reported to the information to those responsible. His unit was originally scheduled to leave the Bar Lev line (the Suez Canal front) on October 8th. By that time, however, the war was in its second day.

“You have to remember Israel’s mindset at the time,” Reshef points out. “We were drunk with victory after the Six Day War. We were all guilty of hubris, and completely discounted the enemy. ‘Who the hell are they?’ we thought to ourselves. The image I had in my own mind was of Egyptian soldiers fleeing, barefoot, on the sands of the Sinai. Don’t confuse technical preparedness with being mentally prepared. No matter how many times we spoke with the troops, we could never convince them to take the possibility of war seriously.

“Shifting from one psychological state to another is difficult. The sad truth is that the IDF had no defensive plan for the Sinai. There were two schools of thought at the time. Former Chief of General Staff Haim Bar Lev called for setting up fortifications. Generals Tal and Ariel Sharon argued against fortifications and insisted that if they must be set up, they should be small. In military terms, Bar Lev favored a static defense while Tal and Sharon advocated mobile defense. As a field commander, I was clearly on the side of Tal and Sharon. But IDF strategy at the time called for defending every inch of the canal front. I should also point out that the IDF failed to adapt itself to a number of developments that had taken place. First, after the War of Attrition, in the summer of 1970, Egypt violated the cease fire and deployed anti-aircraft batteries, thereby denying Israel control in the air. Secondly, though we had obtained access to Egypt’s war plans, the IDF simply did not understand those plans and failed to prepare a response.

“When Egyptian President Sadat said he was ready to sacrifice a million men, we did not understand him. He told his generals that he wanted to cross the canal and penetrate the east bank to a distance of ten kilometers. He saw the war as a means towards political ends. We acted as if the Egyptians wanted to reach Tel Aviv. That thought never crossed his mind. It is true that Egypt also had plans to take the entire Sinai, but they knew this was not realistic.

200 Planes Overhead

Where were you on the first day of the war, October 6?

“At 12:30 in the afternoon we were told with certainty that a war would break out. I told my driver that war was coming. He replied ‘it is good to die for one’s country.’ I answered, ‘you fool, it’s good to live for one’s country.”

“At 1:47 pm we heard sirens on our radio frequencies, indicating that Egyptian planes had crossed the canal. Simultaneously, 2,400 Egyptian artillery cannons opened fire and over 200 jets started bombing us. The entire Sinai peninsula shook like and earthquake. Our tanks immediately headed out to their firing positions.

“To give you a sense of how surprised we were, I’ll tell you a story. After the war, I was told about a tank commander who, while the earth was shaking all around him, asked if he should load a shell into his cannon. In some cases, Egyptian soldiers who had already crossed the canal fired on us even before we reached our positions. Meanwhile, they launched Sagger missiles at us from across the canal, 3.5 kilometers away. Three tanks under the command of Ronny Weiner were hit even before they reached firing position.”

Reshef relates that two and a half hours after the outbreak of fighting, 23,500 Egyptian infantrymen crossed the canal. “Israeli forces, all told – those manning the outposts and our own two platoons (mechanized infantry and reconnaissance) – numbered only 500. It was terrible. The numerical imbalance is impossible to comprehend. Within the first 18 hours of the war, 90,000 Egyptian soldiers and 800 tanks crossed the Suez Canal.”

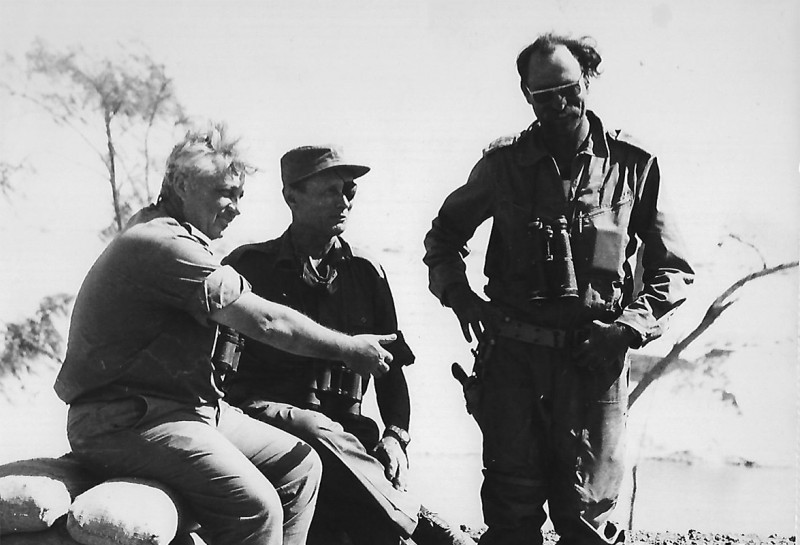

“Let me illustrate,” he continues. “Twenty kilometers separated the Purkan and Matzmed strongholds. An entire Egyptian division crossed the canal in that gap, virtually unopposed. The soldiers of the 14th brigade literally stopped the enemy with their bodies. On the second day of the war, our brigade came under the authority of Ariel Sharon, commander of the 143rd division. We were also reinforced by two battalions. I reported to Arik that out of the entire brigade, we only had 20 tanks left. But we kept fighting.”

In his book, Reshef he brings two different descriptions of his own meeting with Sharon on October 7. The first is from Sharon’s autobiography, Warrior. “After a long and bitter night Amnon was exhausted. Still he kept his cool and had the presence of mind to offer a detailed description of his encounter with Egyptian infantry.” The second account is from Uri Dan, the journalist who followed Sharon throughout the war. “Everyone is silent. Only one person speaks: Amnon, the brigade commander. A young colonel, no more than 35 years old, the fatigue and tension is noticeable on his face. Arik interrogates him quietly. Both men keep their cool.”

Caught up in a major catastrophe, Sharon and Reshef – like the IDF as a whole – acted furiously from the very first minute to execute plans for evacuating the canal forts. One of the strongholds Reshef spoke with was Purkan, manned by 33 reservists under the command of Maj. Meir (Meirka) Weisel. A member of Kibbutz HaLamed Heh, Weisel would subsequently be awarded a citation from the commander of the southern front for his resourcefulness, initiative and outstanding leadership, in recognition of his success in preventing the capture of his soldiers by Egyptian forces.

Initially, Sharon had ordered Col. Haim Erez, commander of another armored brigade, the 421st, to evacuate Purkan on October 9. As soon as Reshef heard this, he called Sharon and asked to evacuate Purkan himself.

“I asked Sharon for the assignment because these men had served under me before the war, and because I had been the one to plan the evacuation route. Sharon agreed immediately,” Reshef explains. Reshef and Weisel agreed that the soldiers would march 10 kilometers under the cover of darkness, cross enemy lines and meet up with the evacuation force the next day. Reshef instructed Maj. Shaul Shalev, commander of the 184th battalion, to organize a small evacuation force. It would include two tanks, four armored personnel carriers, a doctor, medics and a mechanized infantry platoon headed by Maj. Shlomo Levine. Erez’ brigade (the 421st) would provide cover. Reshef decided to put his life on the line and personally lead the small evacuation force. He told Weisel to fire green flares to help locate the soldiers.

At the critical moment, however, Reshef’s force came under massive fire of different kinds from all directions. “It was madness. The evacuation took place in broad daylight,” Reshef explains. “I was really ready to die. I thought I wouldn’t make it. They’re firing rockets at us and we’re maneuvering zig-zag to avoid getting hit. We were in a frenzy.”

At one point, Reshef relates, he came upon a group of soldiers. Thinking they were his evacuees, he duly reported it over the radio. When he reached within 100 meters of the force, however, he realized they were Egyptians.

“I opened fire with my own, 30 caliber tank mounted machine gun, while brigade communications officer, Maj. Shlomo Wachs, fired his Uzi. We threw grenades and ran over them with our tank treads at zero range. Suddenly, after the charge, I found myself alone on top of a hill. I grab my binoculars and see what looks like a monster coming at me, with a cannon sticking out of it, and dozens of soldiers piled on top. It turned out to be the soldiers from Purkan, who had climbed aboard Shalev’s tank and escaped unharmed. I did not see the four armored personnel carriers (APCs) that were part of my evacuation force.

“I asked Shalev where the APCs were. He said they had all been hit. I couldn’t believe it. I asked him again, and he repeated that tragic report. The evacuation had taken a heavy toll: five dead and 28 injured.”

Several hours later Reshef suffered another blow. Maj. Shalev, hero of the Purkan evacuation, had been killed while leading a charge to evacuate a stranded tank crew.

As a result of the 14th brigade’s heavy losses and the reinforcements that had to be sent in, Reshef commanded no less than 18 battalions over the course of the war, 9 of them simultaneously (a regular brigade consists of 3 battalions). On October 15 the brigade was ordered to lead Sharon’s division (the 143rd) in breaking through Egyptian lines and creating a corridor to enable Israeli forces to cross the canal. Sharon had four brigades: Reshef’s standing brigade and three reserve brigades – the 600th armored brigade, under the command of Col. Tuvia Raviv, whose job was to create a diversion; the 247th brigade under Col. Danny Matt that would cross the canal on rubber boats and establish a beachhead; and the 421st brigade, under the command of Haim Erez, whose job would be to drag the bridging equipment necessary to cross the canal. After being reinforced, the 14th brigade now numbered seven battalions: four armored and three infantry and paratrooper units. From the 20 tanks remaining after the first day of battle, the 14th now numbered 93.

Units assembled and reassembled almost spontaneously, as the following story illustrates. Shortly after he left a staff meeting with Sharon, two officers approached Reshef’s jeep. One of them was Lt. Col. (res.) Micha Ben Ari, who had served under Sharon in the famous 101st commando unit in the 1950’s. “He told me he had just come from the Golan Heights, looking for the war, and wanted to join up with a unit fighting in the Sinai. I asked Arik for permission to take his battalion under my command, and he agreed immediately. This was one of two paratrooper battalions in my brigade.”

No one in the 14th brigade, however, could imagine the hell they were about to enter on the night of October 15.

Like Hail on a Tin Roof

The division as a whole suffered from a dearth of accurate intelligence about the inferno lay ahead. Around 6:00 pm, the brigade started moving. Their destination was a 50 square kilometer zone known as the Chinese Farm. They entered the farm at night. 30 hours later the 890th paratrooper battalion, headed by Itzik Mordechai, joined the battle only, to suffer heavy casualties.

The “Chinese Ffarm” consists of 140 kilometers interwoven irrigation ditches, lined by mounds of earth. For the most part, these were unpassable. Some parts of the farm were covered in swamp where a tank could easily sink up to its turret. As a result, several tanks from the 14th capsized in the course of the operation. The objective was to break through the dense Egyptian line and create a four kilometer wide corridor for Israeli forces to pass through so as to cross the canal.

“We didn’t know where the enemy was,” says Reshef. “I decide to cut right through the Egyptian lines, like a knife, opening fire as soon as I see the enemy.” Under cover of darkness, Amnon’s forces proceeded for two hours without being discovered. “At 9:12 pm, I suddenly come upon the enemy camp: bonfires, burned out vehicles, trucks, tanks. It was a logistical center for an Egyptian division. Now I’m surrounded by dozens of Egyptian soldiers, just meters from my tank. I find myself performing three jobs simultaneously: I’m a brigade commander, a tank commander and a regular soldier. The bullets hitting my turret sounded like hail on a tin roof. I have one machine gun and dozens of Egyptian soldiers trying to kill me. An enemy jeep lurches towards me. I open fire and destroy it. In the middle of the night five tanks approach me. I think they are friendly. At 30 meters I realize they’re Egyptian. I order my crew to open fire. In rapid succession we destroy them all with our cannon. At 9:43 in the morning we took the Tartur-Lexicon road. This was the first time I yelled “cease fire!”

Reshef continues with a description of evacuation efforts. Tanks, like that of Platoon Commander Rami Matan, went back and forth, evacuating the wounded and the dead. After the war I interrogated him. Matan, in the tradition of modesty he learned at the military academy, gave a laconic description of events, and did not receive a citation. The truth is he deserved no less than the Medal of Valor. During a moment of calm I went up to battalion commander Amram Mitzna’s tank. He had been waiting to be evacuated himself. I kissed him on the forehead and went back to my tank. Only later on did I discover, after analyzing aerial photographs, that the area had been covered with 3,000 Egyptian infantry fire positions.

During the bitter fighting at the Chinese Farm, the various units of the 14th brigade lost 121 men. Sixty two were wounded. Of the 93 tanks with which it entered the farm, only 36 were left at the end of the battle. Two days later, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan visited the burned out wreckage of the battlefield. He arrived in Sharon’s armored personnel carrier, while Reshef related what had transpired. In his autobiography, Dayan described the horrors he saw that day. “I’m not newcomer to war, but I have never seen horrors like this. Not on the battlefield, not in a picture, not in the movies. One, vast killing field, extending as far as the eye can see.”

All Because of One, Small Jeep

Reshef criticism of military intelligence during the war is withering. In his book he goes so far as to call it “criminal negligence.” He emphasizes over and over again that the IDF did not provide sufficient support for the canal crossing effort that changed the entire direction of the war. The air force, he says, made two flyovers per day to take photographs, but these photos never reached those who needed to see them. The major failure of Israeli intelligence was its inability to understand that the main threat to Israeli tanks came from enemy infantry. Reshef investigated and discovered that the photos never reached their destination because there were no jeeps available to take them. “Idiots!” he proclaims. “They should have brought us the photos by helicopter.”

Reshef has mostly praise for Sharon, with whom he worked closely during the war. Sharon, believes Reshef, is responsible for the dramatic turnaround in Israel’s fortunes on the battlefield. Still, he qualifies this by saying that Sharon also had some very strange ideas at the beginning of the war that would have only led to major casualties had they been carried out.

Until three month before the Yom Kippur War, Sharon had served as commander of the southern front. He was replaced by Maj. General Shmuel Gonen (Gorodish) who was later deposed. The Agranat commission concluded that Gonen “had not properly fulfilled his duties, and bears part of the responsibility for what happened.”

I asked Reshef if the Agranat Commission was not too hard on Gonen. He begins his response by saying “We are all guilty” (a statement originally made by then President Ephraim Katzir, z”l). Still, Reshef has his own words of criticism for Gonen. He describes a meeting with Gonen in the war room of southern command. “Gorodish sat on an easy chair. I had thought that, as head of southern command (Haim Bar Lev replaced him on October 10) he would ask his own brigade commander what had happened on the battlefield, particularly since the 14th brigade had been fighting from the very start of the war. You must remember that by this time, we had lost over 100 men. Gonen, sitting opposite me, did not ask any questions or express the slightest empathy.”

During our interview, Reshef’s usually dispassionate demeanor betrays true emotion when praising the brigade’s officer in charge of wounded soldiers, Dina Zeltz, who received the Chief of Staff’s Citation for her dedicated efforts during the war. He also is full of praise for his former wife Yehudit who, with five children to care for, helped the brigade’s wounded and the grieving families of its fallen.

Many painful visits are burned into Reshef’s memory. He recalls, in particular, one visit to wounded soldiers at Soroka Hospital in Beer Sheva after the war. Many of them suffered severe burns. It was nevertheless heartening to see them proudly wearing the insignia of their unit on their pajamas.

He also remembers an awkward encounter during a visit to the Givat Shaul military cemetery a few months after the war. By this time he was already a Brigadier General. “As I took part quietly in the ceremony, someone I didn’t know came up to me and said ‘I’m gonna kill you and Dayan.’ I told him I’d like to speak with him after the memorial service. He answered ‘I have nothing to discuss with you.’ I subsequently was able to obtain background information on him. It turns out that his son, a tank commander, had come to reinforce the brigade and was killed on the second day of the war. I tracked down his address in Ramat Gan and made my way to his house one evening. I politely asked permission to enter. As our discussion proceeded, he opened a bottle of whiskey. We ended up talking until two or three in the morning, taking leave of each other with tears and embraces.”

I ask Reshef if he knows how many shell shocked soldiers the brigade suffered. “At the time,” Reshef replies, “we were unaware of the phenomenon.” He divides victims of shell shock into two categories: those who remain in denial and refuse treatment for many years, and those who show signs of trauma only years after the events. “No one who experienced the war has remained the same. We have become purer, more open, more sensitive and emotional, more human.”

Reshef is convinced that it was the outstanding bravery and the willingness of IDF soldiers to sacrifice themselves that brought about Israel’s victory, a victory that ultimately “led to peace with Egypt,” as he ends his book. It is a conclusion he cannot emphasize enough.”

[su_note note_color=”#fbfbec”]The Brigade Commander’s Speech on the Eve of the Fateful Battle Reshef: It is a great honor to lead this brigade, and the IDF, to victory.

The 87th reconnaissance battalion was a reserve, armored battalion in Sharon’s division (the 143rd). It was set up six months before the war. Three days after the outbreak of hostilities, its commander, Col. Bentzi Carmeli, z”l, was killed by shrapnel from an artillery shell. Reshef immediately appointed Maj. Yoav Brom to replace him. Fifteen minutes before setting out for the battle to cross the canal on October 15 (Operation Stouthearted Men), at 5:45 pm, Reshef spoke to his troops. The confident tone of his words comes through clearly in recordings that can be found on the website of the 14th brigade. Reshef’s speech is often quoted in IDF commanders’ courses. The job of the reconnaissance battalion was to lead the attack force. After telling them about positive developments on the Golan Heights and in the Sinai, Reshef offered the following words of motivation:

“Yesterday we battered their armored division, causing major damage. We are now poised to launch a flanking attack, from the side and in the rear of the Egyptian army, after which two of our own armored divisions will enter Egyptian territory. We believe this wedge, which we will drive into the throat of our Egyptian enemy, will bring about their collapse. It will not happen overnight but it will cause the enemy to collapse, disrupt the existing balance and, slowly but surely, break the Egyptians. Yesterday, the reconnaissance battalion carried out a superb attack on the Egyptian flank, straight out of the literature of tank warfare. Today, your reconnaissance battalion – our battalion – is leading the way for the IDF as a whole. This is a great honor. I have served as a reconnaissance battalion commander, and I knew what people expected of me. I want you to know that we all expect the battalion to meet its objectives, carry out its missions and lead the brigade and the IDF to victory. Let me repeat: we will not defeat them in one day. But by this action, we will have set in motion the beginning of the end. This afternoon I spoke with the Chief of Staff and the senior generals of the IDF. I inspired them with confidence. I was able to do this after witnessing your fighting spirit on the battlefield. I am convinced that during this battle, we will prove that the hopes that are pinned on us will be realized.”

After the speech, Deputy Battalion commander Zvi Aviram, turned to the soldiers assembled and said, “To battle! Let’s do the job!” In response, men cried, “To battle. . . to battle. . . to battle!”.

Yoav Brom, z”l, led the reconnaissance unite for eight days before he was killed in the Chinese Farm, only ten hours after he and his men listened to Reshef’s speech. [/su_note]